Published on

July 2, 2015

Category

Features

How can we be sure of the colours we are seeing? Testing the limits of perception for a month at The Vinyl Factory’s Brewer Street Car Park, Carsten Nicolai’s unicolor marries psychology, art and music to create an immersive audio/visual experience. Dorothy Feaver caught up with the German artist, musician and label boss to find out more.

Words: Dorothy Feaver

Carsten Nicolai’s prolific inventions as an artist in both the gallery setting and, under various stage names, in electronic music, see him interpreting codes, symbols and theories of natural phenomena in productions that are as pleasurable as they are penetrating. “Sound can only exist if there is space and time,” he has said, “so sound is a sculptural material”, and he conjures forces such as sound waves – or electromagnetic fields, heat waves or radiation – out of hiding and amplifies the evidence in immersive installations, often on a heroic scale.

Born in the German industrial city of Chemnitz, then Karl-Marx-Stadt in the GDR, Nicolai studied landscape design for five years before founding the acclaimed raster-noton label and going on to rack up a starry list of performances and exhibitions, including Documenta 10, Kassel; the 55th Venice Biennale; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate Modern, London; and Centre Pompidou, Paris. He has made LED light patterns dance across the entire façade of Hong Kong’s international commerce centre (a (alpha) pulse, 2014) and monitored sounds hitting the glass shell of Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, turning them into a laser display (syn chron, 2004). In unicolor (2014), presented here, Nicolai grapples with the mechanical separation of audio and visuals, designing a system that bridges the two with Teutonic precision, but which, while illuminating colour theory, thrives on the hiss and crackle of emotional reaction. He takes a moment in Brewer Street Car Park to discuss the show.

It feels pretty crazy to come off this dense street in the middle of Soho, up a little concrete staircase and find this vast black space. What did you think when you first saw it?

It was a car park then, quite rough. Simple architecture, built for parking your car and for that purpose only, and I liked the long sweep. So the transformation is surprising! The exhibition eliminates the outside, it drags you into a completely different world. But there’s still a functional car park – just imagine that every time a car moves, the building is moving.

The first piece, bausatz noto ∞ (1998), has four turntables, and behind them, a back-lit shelf of translucent coloured records. What do the colours signify?

The different colours indicate different sound material, from the very abstract to the graphic. So there’s white, amber, red, yellow, pink… I wanted to have clear vinyl so they overlap on the wall behind. Some are drones, some are high-pitched digital errors; some are cracked grooves from older records; one is a single sonar sound, like a ping. You have multiple choices for mixing different loops into each other. I’ve been building up my sound library for over 17 years [noton.archiv für ton und nichtton], but this is the first time I’ve pulled out the whole catalogue and created 12 new records, in colour.

Who moves the needles?

The visitor can go to the shelf, pick a record, put it on, choose the ‘a’ or ‘b’ side. I am providing a library for you to build your own tracks.

So you don’t have an ideal combination?

This is not about me. I wanted to make a tool that everybody can use, from non-musicians to musicians, from older people to young kids. Locked grooves have always been part of DJ culture, where they integrate things in the mix, and this is a very basic, analogue way of mixing records into each other, a bit like Lego. You have the option to play the same colour record four times and then slightly change the pitch up or down and make it slower or faster. It’s important that visitors listen to the sounds. You can create something quite surprising if you’re good, if you know a little bit and you stay. It’s a very playful situation.

How many variations are there altogether?

Infinite!

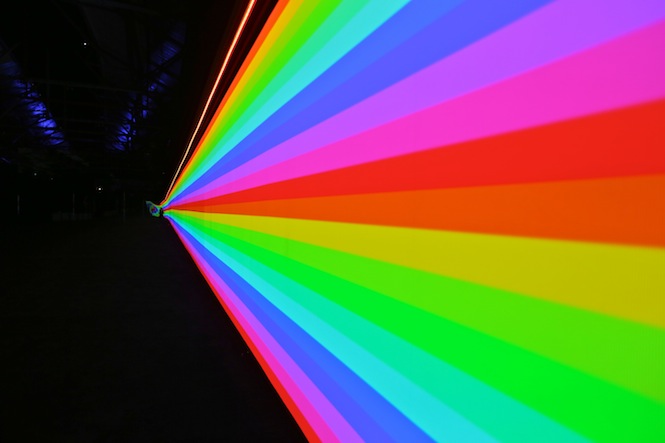

Your new piece, unicolor (2014) also has an element of infinity. In the installation, the visuals are reflected by mirrors on either side; like a rainbow, you never see the end.

Yes, the spatial aspect is very important – you sit here and create this infinite stripe of colour. The projection is 25 metres long but if feels like you can see at least a kilometre.

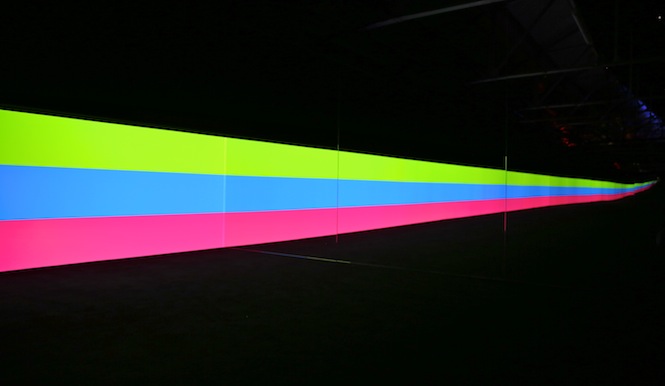

Right now we’re looking at a projection of three bands of colour – red, green and blue… although maybe I’m seeing something different to you.

unicolor is based on the way we perceive colour. This is one of 16 modules, each presenting a different idea of colour perception. You can see that if the RGB is moving fast it turns white because at a higher speed, our brains mix the colour automatically. It’s a bit like a movie – you have 25 still frames per second but we think the image is moving. Goethe realised, almost 200 years ago, that the brain adds colour with a very simple test: if you look at a strong colour for a long time and then you look at white paper, you see the complementary colour. Our perception of colour depends on contrasts of black and white, and what colour is next to it. You can find contrast situations every day in nature: when you look at the sunset, for example, there’s a contrast on the horizon. Well one of the most important points in the installation is what looks like a horizon, where the projection meets the black wall. When you focus on this point, a bit further below, the colours look completely different. For a very short moment there’ll be an afterimage.

How does the sound element change in time with the colours?

The starting point was the connection between white noise and white light: they both have all the frequencies inside. With white noise you are listening to all the frequencies and white light contains all the colour frequencies. A programme translates the sound so that it changes more or less according to the parameter of the colour projection. You can see that the white noise goes with the white visual, but as the visual frequencies are assigned to red, purple and yellow, so too the amount of white noise fades.

If the modules present classic examples of colour theory, how does unicolor differ from a diagram illustrating the science?

For me it’s not science that’s important so much as nature. But this piece is not trying to teach people something. The modules are triggers for the imagination. I want to test how aware we are of the reality that we unconsciously create.

Looking at the melting panels of colour makes me think of Rothko…

And Josef Albers, or Kandinsky… there is a huge line of artists going back to Goethe and, to mention a scientist, Hermann von Helmholtz. There didn’t used to be a big division between scientific research or observation of nature and being a writer or an artist or a painter. I’m not so keen on a completely specialised world because we are people with multiple interests.

What about where you’re making music as noto or alva noto, rather than under the name Carsten Nicolai? How does that feed into what you are thinking about in the art studio?

I don’t make this division; it feels very connected for me. It’s more a problem on the outside – people always want to put you in a box. When I play at a music festival I’m the same person as when I have a show in a museum, though it’s completely different how people see it and what kind of people go there. But I’m enjoying the double life because it creates a situation where I can drop out sometimes. We all know that feeling where you sometimes feel stuck on one place and you move to another place – like a ying-yang.

Going back, is it fair to make a connection between your analysis of nature and your training as a gardener?

Yes, it’s very connected. Normally as a boy at that time you had to do military service. I dropped out – but since I had to wait a year to do landscape design, I started teaching other people who wanted to become gardeners, without knowing anything about it! It was a great year.

How did you know what to do? You had to make up some theory?

No theory, just pure gardening. It’s not difficult; there are different tasks in different months. When it came to landscape design, that was a way more complex study – we were educated to redesign landscapes from scratch, landscapes which had been exploited and destroyed by industrialisation, such as mining systems, landscapes which took a long period of time to stabilise. I learned to see a landscape as a biotope, where the smallest factor could decide if the landscape would collapse or survive. In Europe almost every landscape is completely defined by industrialisation and man’s influence. Even if sometimes you don’t think so, it is.

Like the optical effects of unicolor, things aren’t as they seem?

But this is different because unicolor is about perception, whereas with nature you realise that things are really strongly connected; you cannot make a decision on one topic, without affecting another.

Where do you see this flow of research taking your understanding of light and sound?

To even more basic things. It’s a journey, and if I knew where it ended, I’d probably stop working. Most of the time one thing leads to another, but over years you realise that you’re circling around a topic.

unicolor is on show now at The Vinyl Factory’s Brewer Street Car Park space until 2nd August. Open daily (closed Mondays) 12-6pm free of charge. Click here for more info.

To mark the exhibition, Carsten Nicolai is also releasing a limited edition vinyl. Random Groove is pressed to fluoro pink vinyl and available to order here.