Published on

May 16, 2013

Category

Features

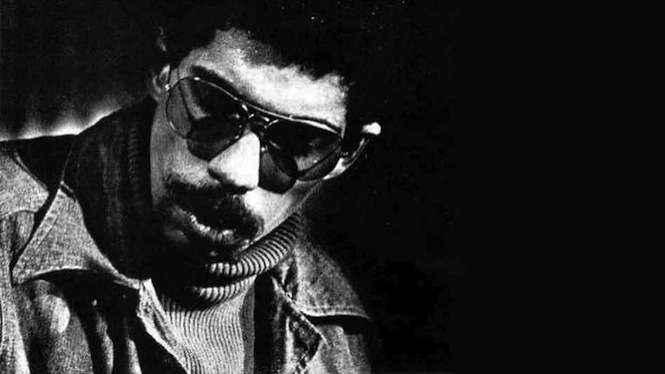

True to its lofty title, the “Experience of Creation” production workshop by Theo Parrish in honour of the late jazz drummer and Miles Davis/Four Tet collaborator Steve Reid provided many important life lessons. The Vinyl Factory was there to take notes and remember the contribution of one of jazz music’s great innovators.

Presented by CDR’s Tony Nwachukwu, this was a ‘fly on the wall’ occasion, a warts-and-all insight into the creative process of the seminal Detroit producer in order to raise money for The Steve Reid Foundation, DJ Gilles Peterson’s charity to help musicians in need and promote emerging talent.

“It all comes down to honesty and intention; why you do what you do”.

Started in honour of jazz drummer Steve Reid, who died of throat cancer in 2010 unable to afford the medical care that could have saved his life, The Steve Reid Foundation has enlisted Theo Parrish, Floating Points, Kieran Hebden and Koreless among others to act as Trustees; contemporary musicians with an eye on the bigger picture. “It’s our responsibility to be remind people why we’re doing it” Peterson says. Steve Reid was someone who never needed reminding.

Born in New York’s notorious South Bronx in 1944, Reid picked up the drums at 16, cutting his teeth in the Apollo Theatre House Band under the direction of Quincy Jones and recording with Martha and the Vandellas among others in what would develop into regular gigs as a session drummer for Motown.

The connection with Berry Gordy’s great soul institution would run deep on this evening. Charged with building a track in under three hours in front of fifty eagle-eyed producers and enthusiasts (Dark Sky and Kon to name check a few), Theo Parrish turned to Motown for the raw material.

Gleaning his meandering bassline from Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise”, Parrish exemplified that connection between your branches and your roots. Describing his sampling process – “we chop as we eat” – Parrish went on to flesh out the lineage (and the metaphor) a little more: “we’re talking about black music and there’s a pain that comes in, it comes natural… [This is] the food you eat as you come up, it’s going to inform you”.

As a young man, Steve Reid was also compelled to explored his roots, leaving his spot at the Apollo in the mid-60’s to embark on a three year spiritual pilgrimage across Africa that would prove a formative influence on his sound and attitude to music.

Steve worked hard and by Gilles Peterson’s account was “always passionate and motivated”, two words you’d readily attribute to Parrish as he sat mic in hand, entertaining a crowd that hung on his every word.

A maverick and a great showman Parrish set his track at 116.8bpm (“everyone does the whole numbers”) and embraced the imperfections of the production process (“you have to work against the machine if you want it to sound human”), a trinity of water, beer and espresso at his side.

First he nabbed the samples – “the sounds within the sounds within the sounds” – from a stack of vinyl that included Stevie Wonder’s Songs in The Key of Life and Marcus Valle as well as Steve Reid’s own Odyssey of the Oblong Square. Fed through his MPC2000xl Parrish built up layers of syncopated highs, mids and lows, rhythms and melodies, straight 4’s and out-there snares into a dense ‘cake’, only to pare the whole thing back down in the mix. Having created a block of sound he carved sections away like a stonemason, revealing the form of the track and giving new insight into the title of his 2007 album Sound Sculptures.

And yet, always loquacious and philosophical, it soon became clear that this workshop was as much about the “why” as the “how”.

When the event was opened to the floor for questions an alarming number from self-proclaimed musicians in the audience seemed more concerned with advice about money than music. Parrish, more preacher than producer by this point, laid down the fundamentals: “If you get caught up in where your music is going to go and whose going to get it then you really limit yourself when you’re making it, because you’re not being honest with yourself. Whatever you do it for, do it for those reasons, [because] whether you’re successful or not, you live and die by that”.

“You got to say “fuck the world”, this is something that’s for me, this is something that I do, because it makes me feel better. This keeps me from chopping up people, you know what I’m saying… or punching the bus driver!”

Speaking about the charity, Gilles Peterson echoed these sentiments. “My whole premise with the Foundation was really just to celebrate this man’s life and his philosophy and ideology”.

It was an ideology that often landed Reid in trouble. In 1969, following his return from Africa, he stubbornly refused to register for the draft on grounds of conscientious objection only to find himself sentenced to four years in prison. He spent the two years he served teaching Black history and music courses to fellow inmates.

Reid returned to the scene in a big way in 1974, founding the Legendary Master Brotherhood collective and his own label Mustevic Sound Inc. as part of the first wave of African-American artists groups (like Tribe and Strata in Detroit and the AACM in Chicago) to take control over their financial and creative independence.

It was a brave and innovative act that Theo Parrish, owner of first Sound Signature and now Wildheart Recordings, readily connects with: “In Detroit you throw a rock and everybody’s got an independent label. I couldn’t see myself being a gun for hire and let somebody run with my musical output.” Without the gains made by Reid and his contemporaries twenty years before SS001 Musical Metaphors dropped in 1997, Parrish would have found it much harder to go it alone.

Reid managed to balance his own pan-African free jazz with session work for bona fide big names from across genres. Work with Marvin Gaye, Dionne Warwick and Jimi Hendrix was supplemented by sessions with compatriots at the forefront of the Afro-futurist avant-garde Sun Ra and Albert Ayler. In ’86 he would even work with Miles Davis on what was arguably the trumpeter’s last great studio recording Tutu.

However, Reid’s career was not just defined by those with whom he shared a stage. In 1976 and 1977, he released Nova, Rhythmatism and Odyssey Of The Oblong Square as a leader on Mustevic Sound Inc., all of which have since been reissued by the jazz arm of Soul Jazz Records Universal Sound.

As Peterson remembers: “He was totally un-money motivated, he really was about the art and the music and the cultural exchange”. Never more so, it seems then when his career experienced an Indian summer in 2006. “I was just amazed because he [Reid] searched me out” said Peterson. “He was living in Holland at the time and he heard about this guy who was playing weird jazz and electronic music in England and he sent me his music”.

It would prove to be a fruitful relationship, with Peterson introducing Reid to producer Kieran Hebden for a series of Exchange Sessions, and the LPs Tongues and NYC. In Hebden, Reid claimed to have found his new musical soulmate with their utterly unique mix of modern avant-garde electronica and scuttling, improvised percussion still streaks ahead of its time.

The bridge that Reid made to the younger generation is a crucial part of what Peterson envisages the Steve Reid Foundation to be about. “There was a double meaning really to what I’m doing here, which in a way was an excuse for me to be able to put some of my energy into a more charitable cause and also to motivate and encourage other producers and DJ’s that it’s not just about themselves”.

While the money raised from the “Experience of Creation” workshop will go straight into the pot at the Steve Reid Foundation, the role of the charity is about more than just money: ”A lot of the jazz generation worked so hard just to make a living and had it hard” says Peterson, “so it’s important to educate the next lot and use our experience to give some guidance to people who might look for it”. Is he optimistic? “I think the new generation have got the right essence now that it’s independentized because of the break up of the music industry. I think people have to find a way of DIYing”.

As for Theo Parrish, his reasons for supporting the Foundation are crystal clear: “Because it’s coming from a place of honesty… it’s something that I think is worthwhile. Hell, I could use it!”

Click here to donate to the Steve Reid Foundation. Then check out Steve’s full discography here.

Theo Parrish has recently released “Day Like This / Feel Loved” with Tony Allen on his new Wildheart Recordings imprint.