Published on

October 25, 2013

Category

Features

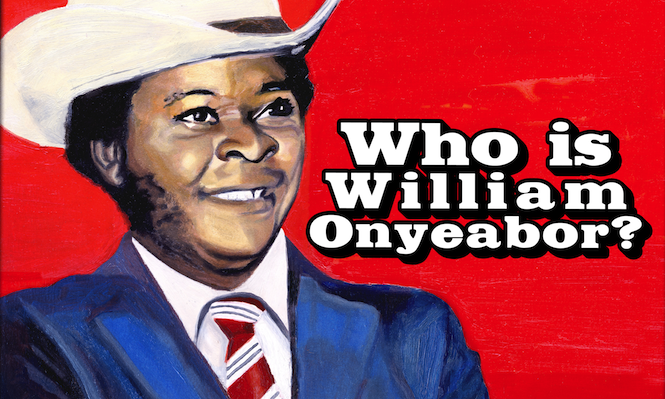

Founded by David Byrne 25 years ago, intrepid world music label Luaka Bop are on the verge of releasing their most mysterious and beguiling record to date. This is the story of their search for cult Nigerian synth maestro William Onyeabor.

Luaka Bop’s President Yale Evelev remembers the moment that making a record with William Onyeabor became a possibility:

“We’d just finished putting out a record by Tim Maia which took me ten years to get released, so I was pleased to have a record that was only going to take three months. I thought ‘this is fantastic, it’s going to be really easy’”.

That was 2008. When I speak to Yale and his colleague Eric Welles-Nyström at Luaka HQ earlier this month their excitement about the release is infectious. And why not? They’re on the brink of something pretty special.

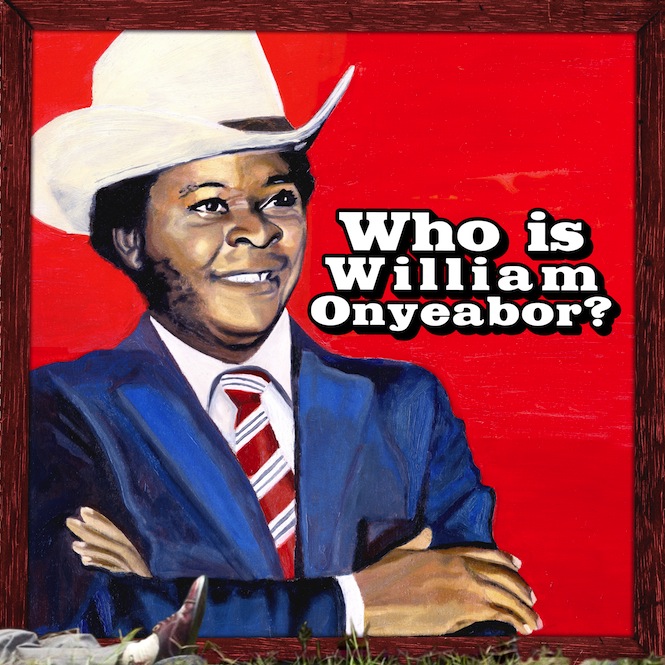

Who Is William Onyeabor? is the first solo reissue of any description to be licensed from the elusive Nigerian keyboard player who recorded eight highly sought after LPs on his own Wilfilms label between 1977 and 1985 in a productive but anonymous musical career. Too weird for the Lagos disco circuit, his jubilant strain of synthetic Afrobeat struggled to make an impact beyond the remote south-eastern city of Enugu where he lived. That, as far as either Onyeabor or his largely ambivalent audience were concerned, was just about that.

However, aside from the records, of which the very few remaining in circulation trade for large sums on eBay and Discogs, Onyeabor left the seed of a myth that has flourished in his absence and whose origins are still unclear. Resurfacing on Strut’s 2001 Nigeria 70 compilation, Onyeabor’s “Better Change Your Mind” was overshadowed by the few tantalizing sentences that passed for a biography in the liner notes:

William Onyeabor studied cinematography in Russia for many years, returning to Nigeria in the mid-70s to start his own Wilfilms music label and to set up a music and film production studio… William has now been crowned a High Chief in Enugu, where he lives today as a successful businessman working on government contracts and running his own flour mill.

The only other ‘fact’ about Onyeabor in circulation, and by and large the most reliable, is that at some point after the release of Anything You Sow in 1985, he turned his back on music and found God.

“We knew there was this four sentence amount of information about him,” remembers Yale, “but everywhere you look, and there’s a fair bit of information about him on the web, it was all the same four sentences, expressed in different ways”.

Rehashed as gospel on blogs, YouTube comments and reviews (The Vinyl Factory couldn’t resist either), William Onyeabor was quietly earning himself cult status as the forgotten man of African funk; the lone ranger from the provinces who sang about honour (“Good Name”), love in the nuclear age (“Atomic Bomb”) and the power of positive thinking (“When The Going Is Smooth and Good”), and embraced electronic pop and new wave while Fela Kuti and the Afrobeat scene took the heat in Lagos.

“There were very, very few people in Lagos that knew about him,” remarks Eric. Even Fela’s own son Femi, an Afrobeat legend in his own right, had no idea. Outside Nigeria though, in the record collections of dance music’s more open-minded hoarders, the William Onyeabor fan club was growing. Four Tet, Caribou, 2ManyDJs, Damon Albarn, Dam Funk and Oneohtrix Point Never are all avowed disciples of Onyeabor’s sparse, lo-fi, dance music. Trevor Jackson recently told The Guardian that Onyeabor’s “Let’s Fall In Love” “still sounds a million nairas, when ripped from Youtube and played in a sweaty basement.”

“Everyone knows their own little bit but I don’t think we’ve met anyone who has the whole catalogue,” says Eric, for whom the pursuit of the bigger picture became an all-consuming obsession.

In 2008, Yale was approached by Uchenna Ikonne of Nigerian music blog Comb & Razor, who had spotted an Onyeabor track on Luaka’s 2006 World Psychedelic Classics 3 compilation Love’s A Real Thing. Hailing from Enugu, Uchenna promised Yale a whole record by Onyeabor in three months, taking the licensing agreement and an advance to Nigeria to give to Onyeabor. Uchenna ended up spending nine months trying to track and pin the High Chief down, before finally returning to New York empty handed. Onyeabor, as if living out the gospel of “Good Name”, had taken the money and not signed the contract. He would not be bought out.

“So I thought well OK, that’s great… That lasted three years, that stasis,” Yale says. It was the first major hurdle of a project that eluded Luaka Bop’s grasp at almost every juncture. Abridging what was an intensely laborious and frustrating process, Yale picks up the story again with Uchenna, who had organized for a female friend of his to go to Onyeabor’s house and collect the signature in person. After five hours he capitulated and signed the contract. Things finally seemed to be moving forward.

Who Is William Onyeabor? will be released as the fifth of the label’s outstanding World Psychedelic Classics series which has already seen Luaka resuscitate the careers of Os Mutantes, Tim Maia and Shuggie Otis. On each, the artist’s narrative has been as important as the music they produced. “We’re a label that talks about the artists on the label,” Yale says. “Shuggie Otis was pretty unknown at the time and part of what we do is inform people and tell people about stuff”.

The thing is, it’s pretty hard to tell someone’s story if you have never even spoken to them. Having finally succeeded in licensing the tracks, Yale reached out to Enugu-born novelist named Chris Abani to write the liner notes and interview Onyeabor about his music. When informed of the plan on the telephone, Onyeabor dug his heels in. “Why would I want to talk about that?” he protested, “I just want to talk about Jesus”. And then he hung up.

“I really didn’t know what to say to that,” admits Yale, disturbed to the point of distraction by the prospect of having to put out a record with no information on it. “It felt like we were doing half a job and we weren’t really trying hard enough”.

With Onyeabor reticent, Eric and Yale approached everyone they knew who had knowledge of his work and began trying to piece together his narrative themselves.

“Somebody told us that he studied law at Oxford… We heard he was aligned with the government as almost like a gangster character… Somebody else told us he doesn’t actually play any instruments and that he hates musicians,” laughs Yale, who once confronted Onyeabor on the telephone about his supposed enrolment in a Soviet film school. “Film production?” he replied, “I don’t want to talk about that, I just want to talk about Jesus”.

Although the project appeared to be floundering, for Eric, every set back hinted at a truth to be uncovered. Thoroughly obsessed – he once typed out all of Onyeabor’s lyrics to try and find hidden messages – Eric decided to track him down in person. “I was dreaming about him,” confesses Eric, as he prepared for his visit. “I was thinking maybe I could just be really friendly and shower him with love and stories of other artists that admire him. You know, “Four Tet thinks you’re great!” And then Uchenna tells me, “If you do that, he’s going to break your neck”.”

Eric’s mission to meet Onyeabor immediately took the more fantastical elements of the Onyeabor creation myth to a new level. A Nigerian Searching For Sugarman without the candy-coating, his description of the trip smacks more of Cold War espionage than redemptive biopic.

Having been told that Onyeabor lived in palace on the outskirts of Enugu, Eric was initially surprised to find himself deposited outside an empty store front in one of the more chaotic corners of town. It was at this point the scene took its first turn for the bizarre.

“There’s a door which is open, it’s dark inside. I step inside and it’s empty except for a woman sitting by a plastic table on a plastic chair. It looks like an empty office, there’s a counter but there’s nothing around the counter, there’s a clock on the wall but it had stopped. Then she asks “Are you here to see the Chief?”

“Yes, yes, I’m here to see the Chief, My Onyeabor”, Eric replies.

“Are you from Russia?”

Eric remembers how his jaw-dropped, how he explained that he was in fact from New York and was releasing the Chief’s music and how he was then placed in a car and driven into the woods on flooded dirt roads to a stately home with a silver 70’s Mercedes parked outside, where he was welcomed by Mrs. Onyeabor and led through the echoing hallways past rows of dark, cavernous rooms.

“It was so surreal, there were so many things in there that you try and take in.” He smiles at the memory of the retro furnishings, the small windows, fake chandeliers and photos of Onyeabor that lined the walls. There was musical equipment too – a cutting machine for film and music reels, a 24-track mixing board and the odd keyboard. “It’s really like time had stopped in the 70’s. It’s super modern from a certain period of time and then nothing has changed.”

Led up the staircase, Eric happened upon William Onyeabor sunk into a 70’s couch; a giant of a man (whose wrists were too big to fit the watch Eric had brought as a gift) sat watching Nigerian television prophet T.B. Joshua, as he has done most days for the last thirty years.

“I didn’t feel like I could go anywhere near asking a direct question,” says Eric, who spent the best part of a week sitting with Onyeabor, discussing whatever came up in conversation, aware that “he can be very nice one moment and then can totally switch”.

What information about Onyeabor Eric did manage to tease from his visit seems negligible in retrospect, almost absurd in its isolation. Engaging him about Sweden, Onyeabor revealed that he used to import record manufacturing equipment from Swedish company Toolex Alpha and would make frequent visits to the factory in an obscure suburb of Stockholm called Sundyberg where he would go out for dinner with a bloke named Gunnar Axel.

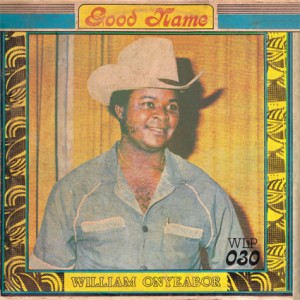

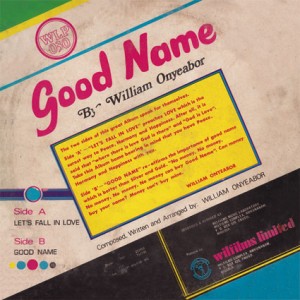

On his last day, Onyeabor proclaimed Eric to be his “American son” and offered to pay for his flight home. Instead, Eric seized the opportunity to ask for one of Onyeabor’s records. Using his intercom button, Onyeabor summoned up a copy of “Good Name”, which he handed over to Eric slowly, pointing to the Wilfilms logo on the back saying “I manufactured all my records with my machines from Toolex Alpha” before gesturing to the record’s title track and singing the chorus while his hands played along in the air.

Eric left Enugu shortly afterwards, having struggled to find anyone in the local area who could remember the musical contribution of their High Chief. The myth was self-propagating, the man a shadow at its core. What did Eric know now about Onyeabor now having spent a week in his company? “Those four sentences [we already knew] and also that he went to Sweden!” He laughs. “I think he went to Denmark too.”

Back in New York, the search for Onyeabor had become the story itself, and the compilation was christened thusly. “It didn’t make sense to me that someone didn’t want to talk about their music, I’d never encountered that before,” laments Yale. “I’ve never had somebody be unhappy being appreciated”.

What sets the story of William Onyeabor apart from the rags to riches music documentaries that have captured the public imagination and dominated film festivals in recent years (Rodriguez in Searching for Sugar Man and Charles Bradley in Soul of America the obvious examples) is that Onyeabor seems to operate with an entirely different set of values. Where heart-warming tales of Rodriguez and Bradley flatter sympathetic elements of the American Dream to right a social and artistic wrong in service of the individual, Onyeabor appears happy to have his “Good Name” preserved in absentia. Of what Eric learned, he was a well-travelled man, proud of the successful businesses he established away from music, whose biggest goal now is converting people to Christianity. Despite his music’s various exhilarating religious and political messages, Eric muses, “maybe he doesn’t feel it is doing that like it should.”

If there is a void at the centre of this project where “Man of Honour” William Onyeabor should stand, Eric and Yale have done a marvelous job of peopling it with an impressive entourage of close to forty collaborators, well-wishers and Onyeabor enthusiasts.

“We try to build things that live”, says Eric, who speaks so passionately about the project it’s hard to not just let him talk at you. “When we interviewed Damon Albarn, any question about Onyeabor he lights up like a little kid”.

Supporting the queues of admirers from western music’s top table (even Pharrell was approached) are foundational synth manufacturers Moog, for whom (of course!) Onyeabor was once rumoured to have been a rep. “They’re making William Onyeabor synthesizers that are being given to a group of these artists making Onyeabor remixes,” explains Eric, that will be released in due course. There’s also a film being made about Onyeabor’s music and a week of events to celebrate the release.

The triple vinyl edition, which had to be remastered 7 times by Yale who shudders when he tells that particularly story, has four extra tracks, including “When the Going Is Smooth and Good”, which lends its name to Luaka’s fictional Onyeabor fan club “The Smooth and Good Club”. “At one point we were looking to print and press in Nigeria,” says Eric. “My dream for a while was that it would say at the bottom “Printed in Nigeria”, but that wasn’t possible.”

Over the last five years, tracking down William Onyeabor has created a myth of its own, the story of which Eric and Yale tell with so much glee it almost seems as fabricated as that of the man himself. But for a grainy photo of Eric in a Lagos nightclub with Nwankwo Kanu, there’s nothing to say the trip ever happened at all. That, of course, is entirely the point.

“For us, it became this project of truth,” says Eric, “trying to understand what was truth and what was our perception of reality”. He mentions Onyeabor’s first record, the movie soundtrack Crashes in Love as an example. “It was the soundtrack for the film Crashes In Love, at least that’s what it says on the record. But we’ve not met anyone who has seen the film”.

“Uchenna tells this story where he asked him about the film and him getting really angry,” adds Yale, who finishes the interview by taking us right back to the beginning. “When this whole thing started with that compilation in 2006, we licensed the track from somebody it turned out didn’t have the rights to license the track at all. It added to the whole mystery of the whole thing.” Whoever William Onyeabor is, we’re happy to believe just about all of it.

Who Is William Onyeabor? is released on 28th October on 3xLP vinyl. For a list of William Onyeabor week events click here.