Meet The Selectors: Haseeb Iqbal

In Meet The Selectors, we highlight the selectors, DJs and music experts that have presented Listening Sessions at the Devon Turnbull Listening Room in 180 Studios.

At 26, broadcaster, DJ, and curator Haseeb Iqbal is reshaping how London listens. From his residency at Devon Turnbull’s Listening Room in 180 Studios to his DIY club nights and Beats & Boards event series at Tate Modern, he’s building spaces for sharing, reflection and joy. VF's Kelly Doherty sat down with him to discuss his experience of the Listening Room, falling in love with London’s music scene and the inextricable connection between music and politics.

"I realised I was going to dedicate the rest of my life to the arts," Haseeb Iqbal recalls of his early teens. "It was where I felt I could be myself seven days a week".

Speaking with Iqbal, it’s hard to picture him any other way. Warm, sharp, and deeply knowledgeable, Iqbal radiates enthusiasm. Whether he’s discussing the purpose of a DJ set or speaking in front of an audience, his energy is palpable. He's a refreshing antidote to every last trope about a grumpy, elitist record collector and gatekeeper. Iqbal's life is a journey into the far corners of music culture and he wants the world to come along for the ride.

Growing up in London, Iqbal was a restless teenager, simultaneously discovering the city and his creative identity. “At around 13 or 14, I was quite a naughty kid at school, fearless and spontaneous. London just opened me up to the magic of life,” he recalls. Hip-hop was his first love as he absorbed the music of Kendrick Lamar, Joey Bada$$, Kanye West, J. Cole and Jay-Z. Iqbal would play them on repeat, studying the lyrics.

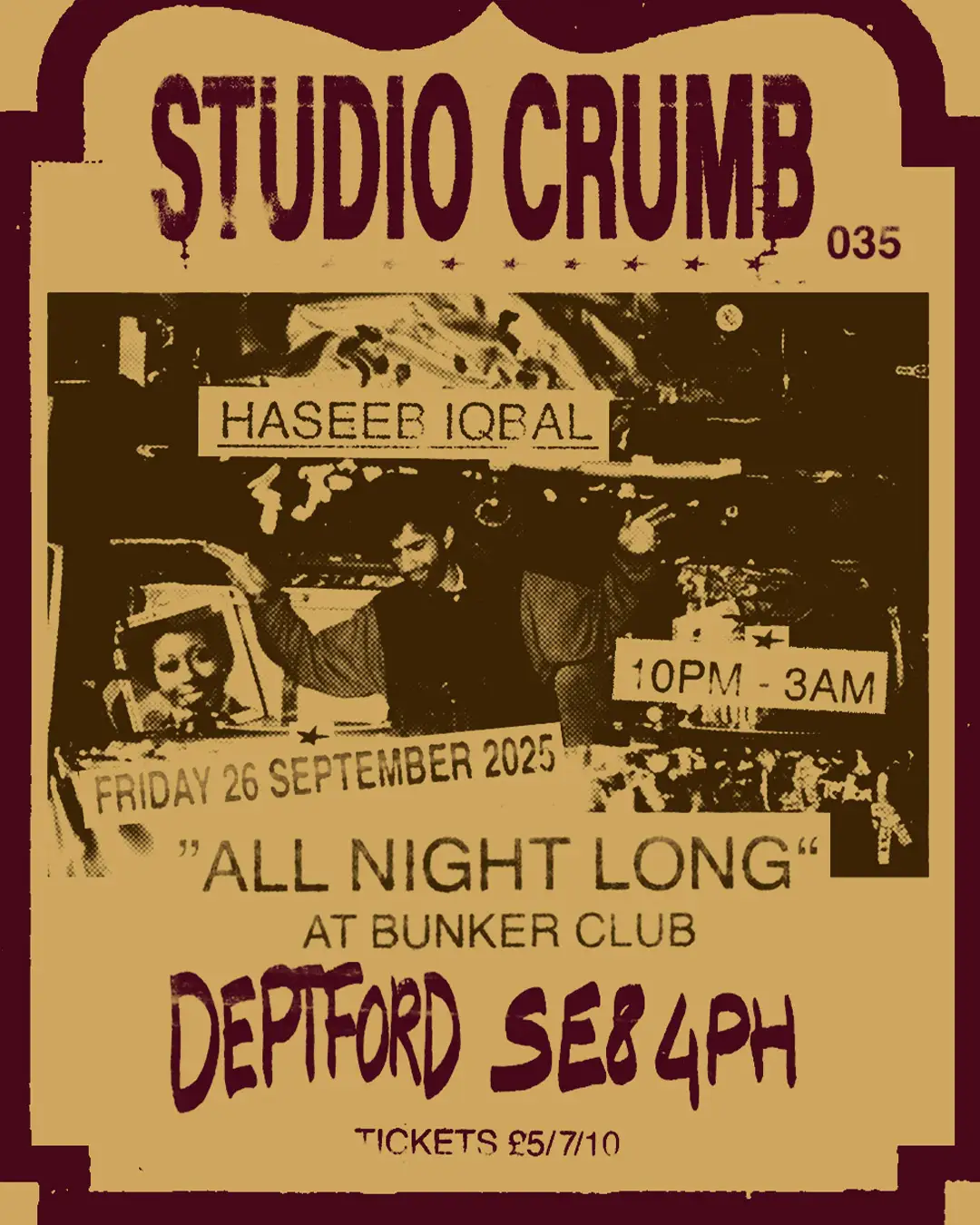

At this time, Iqbal started writing poetry with the fountain pen he still carries everywhere today. Performing his work at open mics introduced him to a growing hotbed within London’s music scene as he attended Brainchild Festival, Total Refreshment Centre, and STEEZ – Sunday-night jam sessions where the likes of Ezra Collective, Nubya Garcia, and Moses Boyd were beginning to play. “I was sixteen, in Deptford, surrounded by all these incredible musicians,” he says. “It was electric".

Unlike many DJs, Iqbal didn’t grow up around records. “I didn’t inherit a collection. I came to vinyl at around eighteen, slowly drifting into record shops just out of curiosity,” he explains. One of his earliest memories is of a shop between Leicester Square and Covent Garden. “I bought The Genius of Lester Young. I didn’t even have a turntable,” he laughs.

Eventually, he saved up for one, along with two discounted Pioneer speakers from a closing Maplin store. “The first record I ever played was Seun Kuti and Egypt 80. It was a crazy moment.” When he arrived at Goldsmiths to study English and Creative Writing, his halls in Camberwell became a HQ for his musical obsession. “I’d listen to records all night,” he says. “It was my first space in London that was entirely mine.”

At Goldsmiths, Iqbal locked into a student society that hosted open-deck nights where young selectors could play twenty minutes of vinyl to a room. “That was the first time I was recontextualising music for a crowd,” he says. “It was incredible.” Those small nights led to low-paid gigs in the trenches at midweek cocktail bars and empty pubs. “Even when no one was listening, I was,” he says. “Those hours taught me everything.

When promoters didn't book him, Iqbal created his own space. His DIY night, which eventually settled on the name Studio Crumb, has become one of London’s essential monthly parties. “The main thing is, I never stopped,” he says. “I never suppressed the excitement.”

At 20, Iqbal joined Worldwide FM, Gilles Peterson’s beloved independent radio station. “That was huge for me,” he says. “I’d listened to it at school, and suddenly I was part of it.” He was the youngest presenter on the roster. “It was like joining a football team. Are you going to crumble, or are you going to bring quality?”.

Soon, Peterson asked him to warm up for jazz legend Gary Bartz at the Royal Festival Hall during the London Jazz Festival. “That’s when I thought, ‘Okay, I can do this,’” Iqbal says. “I brought my parents. I wanted them to see something that made sense of all those basement gigs.”

Another pivotal moment came at East London club Fold, where Iqbal saw legendary soundsystem operator Jah Shaka play through the night. “It changed my life,” he says. “Eight hours of pure vinyl. It showed me the spiritual power of sound.”

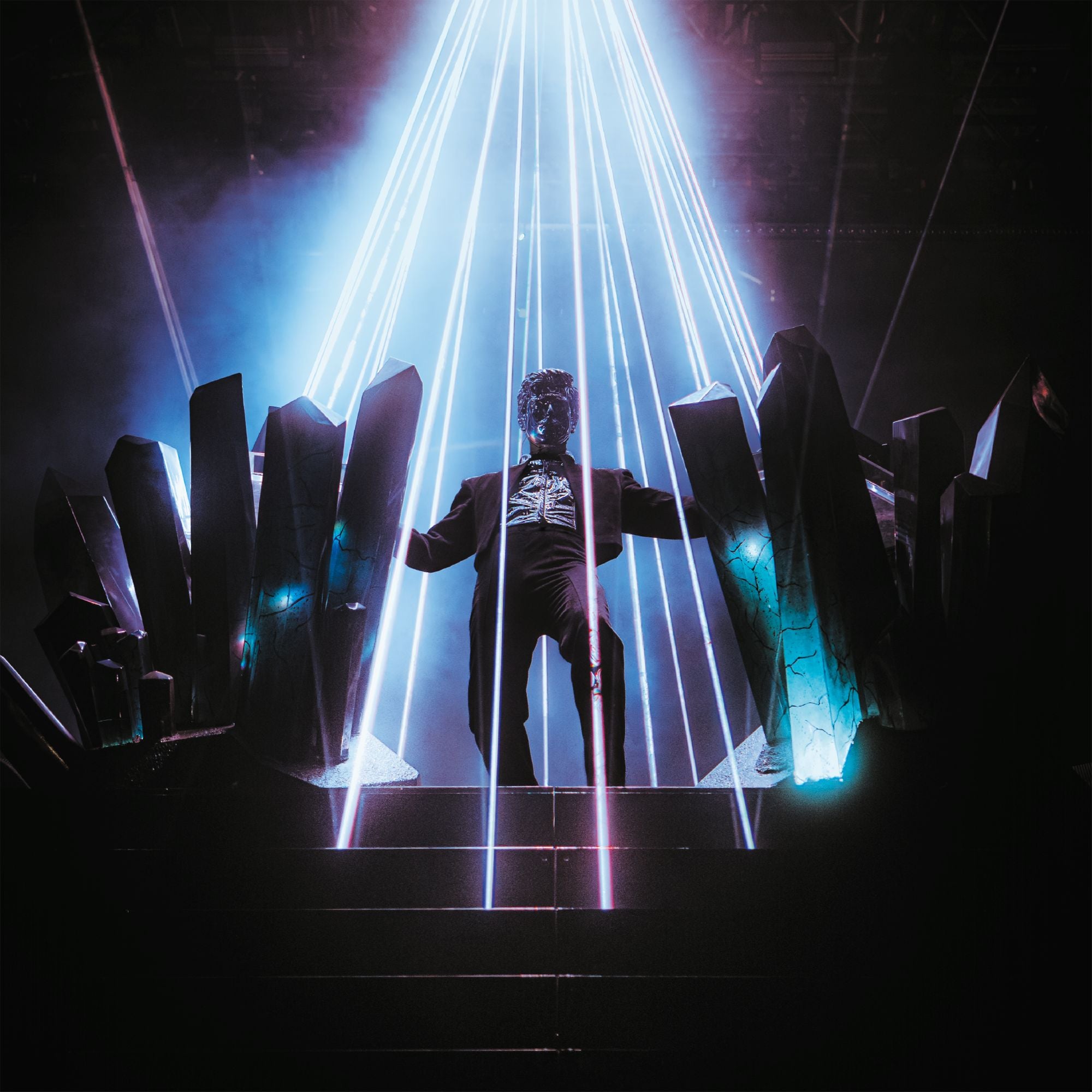

Iqbal brings this same sense of awe every time to the Listening Sessions he runs as a resident at Devon Turnbull’s Listening Room in 180 Studios. “It’s been the most unbelievable residency,” he says. “It’s placed me closer to sound than anything else.”

Each session explores a theme and previous editions include Blue Note Records, Songs of Healing and Resistance, Jah Shaka and Pakistani Cinema Vinyl. “It’s theatre meets sound system culture meets storytelling. It’s brought my love of poetry, theatre, and music together.”

Inside the room, everyone’s shoes are off, phones are on airplane mode and incense burns in the corner. “It’s about slowing down,” he explains. “People say, ‘No one goes as deep into the history as you.’ It’s not just about the records. It’s about understanding where they come from, politically and emotionally.” Across 30 sessions and counting, Iqbal has hosted more than a thousand listeners. “It’s proof that impact doesn’t have to be viral,” he says. “I’d rather touch a thousand people deeply than a million fleetingly.”

Education and politics run through everything he does. “Wikipedia isn’t inspiring,” he says. “The best teachers excite you through storytelling and that’s what I try to do by using music as a touchstone to understand time, movement, and struggle.” In his Songs of Healing and Resistance session, he traced apartheid-era South Africa and Black British uprisings through the music of Hugh Masekela and others. “People forget the Brixton riots came out of the New Cross fire,” he says. “When you tell that story through music, it lands differently.”

Iqbal believes DJs have a higher responsibility than simply curating a vibe. “After an artist dies, they can’t play to big crowds anymore,” he says. “It’s the DJ who keeps their music alive. When I play Gil Scott-Heron in a club, I’m carrying his voice forward.”

He also suggests this responsibility extends to political decisions within the scene. “It's impressive to see people taking note and accountability of the spaces they're playing and opening that dialogue,” he says, referencing the recent boycotts of KKR-owned festivals due to their investments in Israel.

As ever, Iqbal's perspective is centred in discussion and community building. "It's difficult. We're in a world where everyone believes what they read and is more inclined to detach from something with a potential negative thing attached and not engage in any dialogue. That's dangerous. Without dialogue there can be no improvement," he states.

As one of the few South Asian figures at the forefront of the UK underground, Iqbal recognises the visibility attached to his presence. “Growing up, we never saw it,” he says. "I have a lot of brown people coming to me – brown boys and girls – saying, 'Thank you for what you're doing because we've never been able to look at the arts and music and see a brown person that's cool. You're making it cool to be a nerd about music.' That means a lot.” He’s built everything himself with no manager or agent and no shortcuts. “Every record I own, I saved for. Every event I’ve played, I built. Every booking, I chased. So when I speak, I speak from experience."

His independence and community-building allows him to change narratives around who can succeed in London's underground. “The goal isn’t just to exist within these spaces,” he says. “It’s to open the door for others. It's to make sure the next generation of brown artists doesn’t feel like the first.”

Iqbal’s ethos is simple as he urges us to listen deeply, share generously and stay curious. “We’ve got to remind each other that storytelling is how we’ve always understood the world,” he says. “If we lose these spaces, we lose that connection.”

Find out about Haseeb Iqbal's upcoming events and shows here. Learn more about the events at Devon Turnbull's Listening Room in 180 Studios here.